Read the first and second in this series.

A cafe in an urban neighborhood named a’Garden Cafe’ without a garden or any type of seating. Why? Because the name ‘Garden Cafe’ sounds cool.

Similarly, a salon named "Paris Salon" situated on a humdrum street in Mumbai—a far cry from the luxury streets of Paris.

What is it with English names for local businesses?

Being modern seems synonymous with using "English" or being "Western."

Traditional? That’s "Indian"—or socially conservative.

When aiming at students in colleges where the language of instruction is English, what would a store owner choose?

The word café or dukaan (Hindi for shop)?

Cafe, of course!

So, we have strange and somewhat obvious names like ‘Cravings Cafe,’ complete with an Instagram page. Or the national chain Cafe Coffee Days!

Or if English names have become blasé, we are also introduced to the very Italian-sounding, Bel Posto, or the ‘beautiful’ cafe.

What about Lavonne Café in Bangalore and Delhi? Perhaps chosen for its phonetics or mistakenly thought to be French given that the bakery boasts French craftsmanship. In reality, it’s American in origin, derived from La and Yvonne, meaning “archer of God.”

Who knew?

But this fascination with English doesn’t stop at cafes.

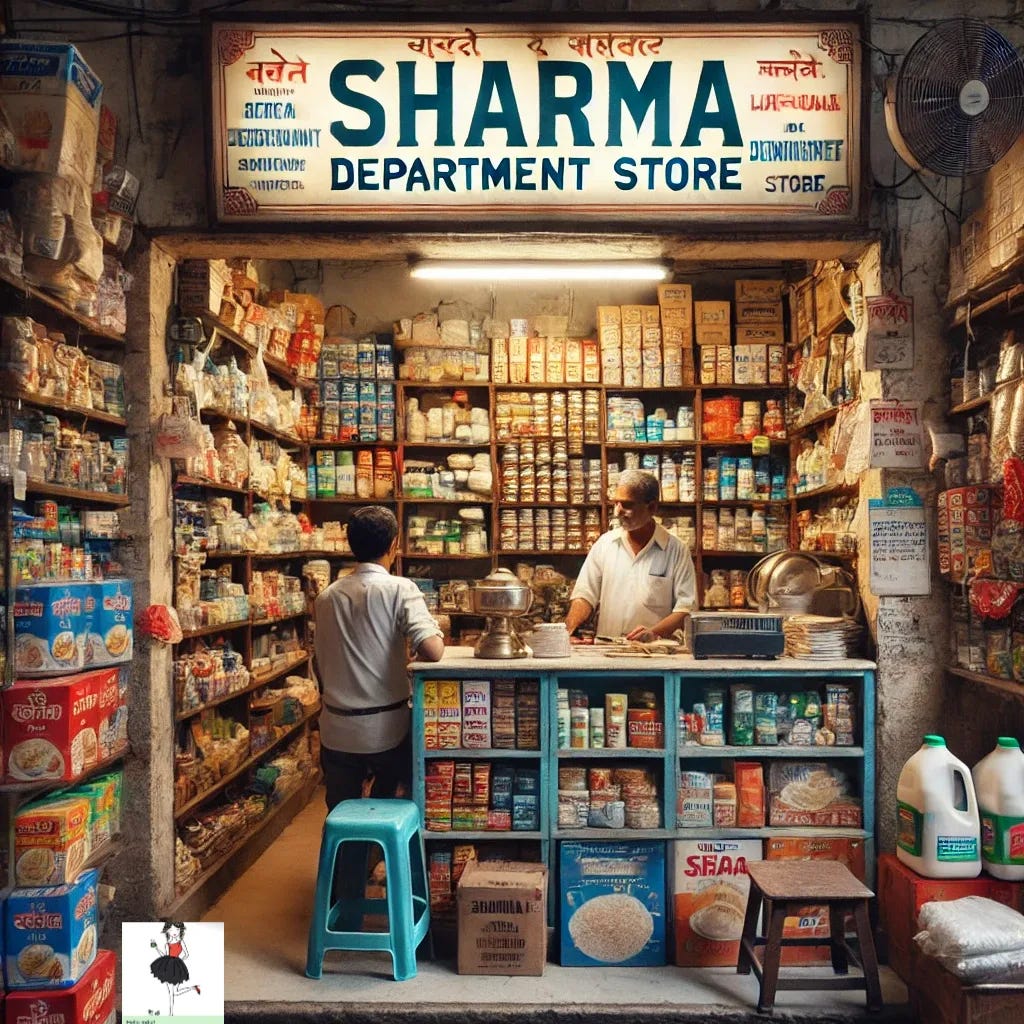

Take, for instance, the ubiquitous "Sharma Departmental Store." In upscale areas, it becomes the more polished "Sharma Department Stores," where Sharma is the owner’s last name.

These neighborhood sundry stores carry everything you might need without requiring a trip to larger markets.

If you live nearby, they’ll deliver—and might even extend credit for a month, collecting dues at month’s end. (This model thrives in Delhi’s neighborhoods.)

This old-school business approach relies on relationships and a shrewd understanding of emerging market forces like online shopping.

For example, a customer, Mrs. Lal might call with her order: “Send 5 kg rice and a small Brooke Bond1 tea.”

The shopkeeper instantly translates "small Brooke Bond tea" into a small box of Brooke Bond Red Label tea.

No modern software required—he knows Mrs. Lal’s preferences from serving her for months and even, years.

He reassures her, “The boy has left.”

“Has left” might mean he’s just leaving or left five minutes ago—but will deliver to three homes before hers.

"The boy" could mean an 18-year-old or a 30-year-old.

Age is irrelevant; the role is what matters.

Similarly, in offices, “office boy” refers to a twenty-something hired for admin tasks.

The term "office boy" likely originated in public offices, where such roles remain common. A special errand they run?

Bringing chai (tea) to the "hard-working" office workers, who may not be able to break during peak hours—or simply because it’s convenient to have tea brought to you.

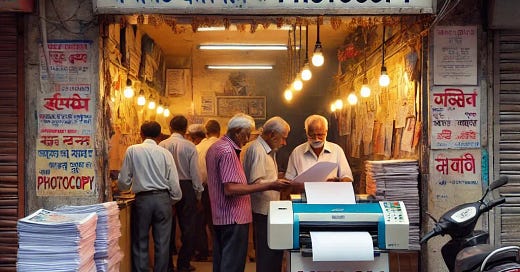

This practical use of English extends to stores offering "Xerox" services—a shorthand for photocopying.

Most “Xerox” shops are small operations with one or two machines working non-stop to cater to customers navigating bureaucratic paperwork.

Others are advanced print shops with sleek, high-tech machines.

Using “Xerox” as a verb in India went unchallenged for over 50 years.

Then, one fine day, the makers of Xerox—derived from two Greek words meaning "dry writing"—decided they needed to address this issue in India.

In 2012, they sought official recognition and successfully won their intellectual property claim to treat "Xerox" as a non-generic term in India.

They also ran ads - quite condescending in tone - in English newspapers and in-flight magazines, which I paraphrase from memory as:

“Xerox is a brand. Copying is the act. Repeat after us.”

Unfortunately, the campaign targeted consumers rather than business owners branding their shops as "Xerox Shops."

You can judge the success of the campaign by the sheer increase in shops still sporting "Xerox" in their signage.

Today, we even have "Jumbo Xerox" shops catering to custom paper sizes!

Neither have the vast majority of Indians replaced "Xerox" with "photocopy" in their everyday language.

But what about its market share? Surely, with such high brand recognition, Xerox must dominate the market?

Unfortunately, no. The Japanese firm Konica Minolta has cornered the local market with a 50% share.

This is akin to the fight for the value of the "Kleenex" trademark in the U.S., where the brand name has become synonymous with tissue.

Or "yoga," a term some argue has been stretched to encompass anything vaguely related to wellness.

Or even "bazaar," once a simple noun for a marketplace, now elevated to grace the title of a luxury magazine.

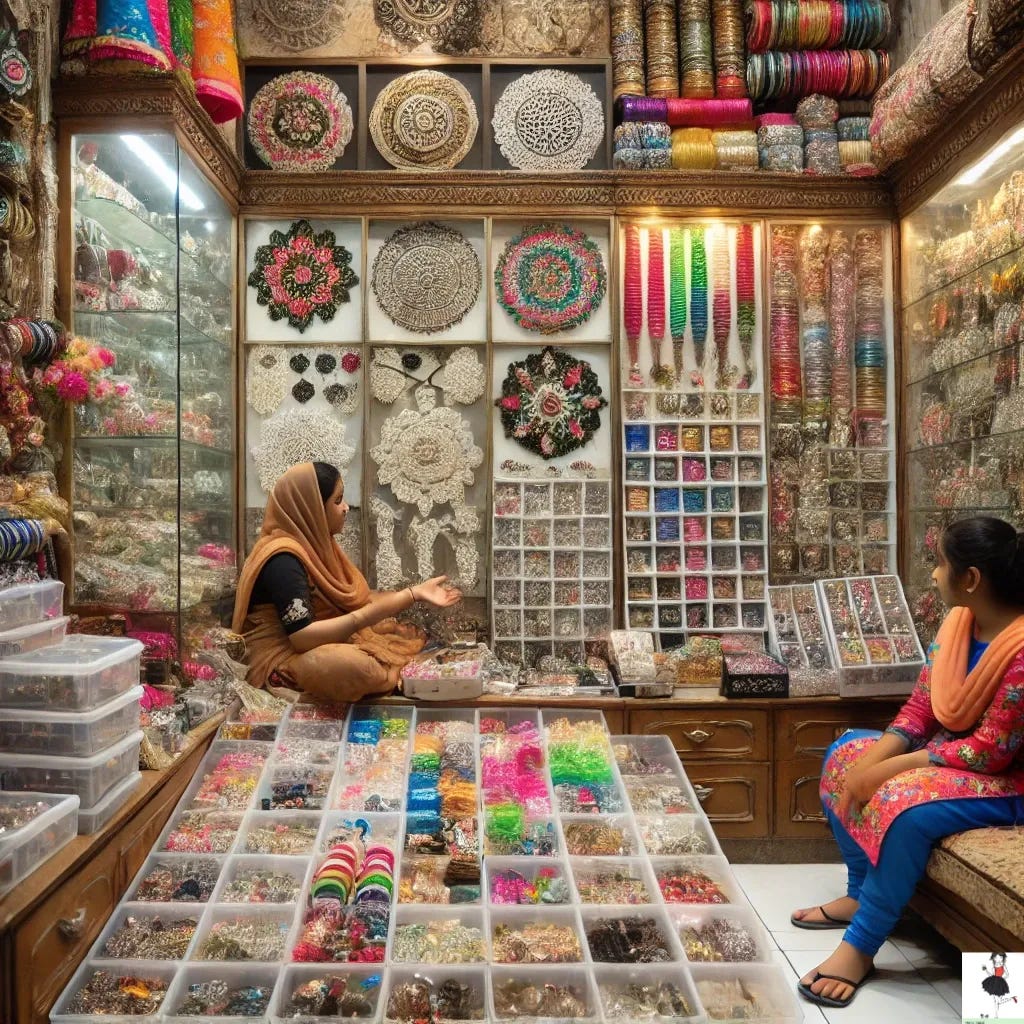

Then, there’s the ‘Fancy Store,’ a type of shop locals recognize immediately.

These stores offer a curious mix of decorative items, lace embroidery, stuffed toys, accessories, bangles, and "artificial" (costume) jewelry, including dazzling arrays of bindis2 in every shape, size, and color.

Each visit is an adventure.

The owner might enthusiastically pull out boxes of butterfly clips or glass bangles, introducing them as "imported from Korea" or "original from Hyderabad."

E-commerce is no match for the hospitality these stores provide—cushioned seats on chairs, small stools, or even futon-style seating on the ground—while customers sift through their treasures. Inventory like hair clips, bands, rings, and bangles is carefully organized in transparent plastic or acrylic boxes, sorted by style and price.

Instagram and YouTube have become lifelines for these stores.

English fluency is less important than mastering the art of digital show-and-tell: modeling wares, creating digital signage in English, and using the right hashtags. Check out this 49-second video of a wholesale ‘fancy store.’

Many women also run these stores, often from their homes, managing the dual responsibilities of childcare and earning a livelihood.

Some stores are better than others, and over time, you’ll know which ones are the best in your neighborhood.

Each store reflects the owner’s personality and understanding of trends—often shared in their networks through word of mouth.

Trips to a fancy store often feel like a practical errand with the added bonus of unexpected finds, as each shop’s inventory reflects its owner’s unique choices.

The best way to navigate one?

Simply ask the owner to show you their finest items. Chances are, they’ll bring out premium, higher-priced goods that promise better quality.

With affordable prices, you’re almost certain to snag a bargain!

Liked this take? Have you come across any quirky English names or phrases that stood out to you?

Brooke Bond is a famous tea brand in India. Its history traces back to its founder, Arthur Brooke of Manchester, England, who added the word "Bond" to his store name when he opened it in 1869, simply because he liked it . Over time, he believed, it came to signify his commitment to quality tea. Many mistakenly believe Brooke Bond to be an Indian brand due to its ubiquity in India’s history. Today, it is owned by Unilever, a multinational company.

Bindis, Hindi. Single and married women traditionally wear these colored dots on their foreheads. As an aside, in the late 1980’s, a wave of fear spread among many Indian communities in New Jersey with news quickly reaching India. Indian women on the East Coast began avoiding visible markers of their heritage - such as saris, and the ubiquitous red dots or bindis - due to the random hate crimes carried out by the self-styled ‘dot busting’ gang.

Walking the evening streets of Fukui, Japan I saw a nice well lit sign in front of a place named "WORST singing+Bar".

Dungarees or blue jeans is Hindi and used to indicate Levi’s now.

Madras, tie dye shirts were very popular. Soft cotton. Like to find one now. Language changes. What was old is new and vice-versa. Lassi the yogurt drink is so close to lassie a young woman. Must be more melting pot words. Really like this challenge you took on for size or sighs.