Once upon a time, deep in a forest in an ancient land, sat a famous sage meditating.

His concentration so fierce that even the Gods in Heaven became afraid lest he acquire powers greater than he already possessed.

So, as it is always with fear, the king of the demigods dispatched his most attractive nymph1, Menaka, to distract the sage and break his tapas2.

At first, all her efforts failed to rouse the sage.

But she was the foremost of heavenly nymphs - a master of the arts, of dance, and of unmatched beauty.

Eventually, she broke the sage’s concentration.

From this union was born a child.

But nymphs have duties in the heavens, and cannot raise children like humans.

Sages, of course, are supposed to stay focussed on progressing the Self.

How does one acknowledge his mistake?

This dilemma could only result in one option, unfortunately for the child.

Abandon her in the forest.

Yet, for every abandoned child, hope arrives in unexpected ways.

Wise birds of the forest gathered around the newborn infant, shielding her from harmful forces.

A kind sage, walking back to his hermitage, saw the innocent baby and was struck by how the birds were protecting her.

He took her to his ashram and adopted her, naming her Shakuntala - for one who was protected by birds.

The girl was raised by the sage and knew no other humans.

Her friends were the animals of the forest - the deer, and the surrounding flora and fauna.

As she grew up, she blossomed into a woman reflecting the inherited traits of her beautiful mother, and spiritual father.

Unaware of her origins, she doted on her adopted father and served him with love.

One day, her father announced his journey to another ashram and advised the girl to be on her guard.

But fate has a way of intervening in lives.

The king of a nearby land, out hunting, alone in the forest, lost his way and searched for a refuge.

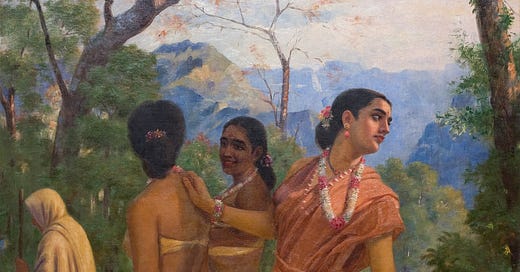

That happened to be the isolated ashram of the sage, and upon arriving, the king saw a woman of unparalleled beauty tending a garden before the hut, while her companion, a baby deer, played nearby. A short distance away, its mother kept guard.

Speechless, the king watched the woman.

For no beauty of this calibre could be of earth.

Then, slowly recovering his wits, he drew closer to address her.

Approaching her cautiously, he first sought her name.

Shakuntala turned at the sound of a strange voice.

She rose to find a handsome king at her doorstep.

Until then, the only humans she had met were her father and his peer sages.

She too was awestruck by this handsome stranger - who was this man, dressed so bewitchingly in kingly attire, holding a bow and arrow lightly by his side, and smiling at her so?

Both were struck at the same time by Kama, the God of love - which was propitious.

The king forgot his duties, and his return to the kingdom.

Shakuntala forgot her environs.

Lost in contemplation of each other, they stood silently.

Until they were called to her world by the baby deer tugging at Shakuntala’s garment.

So it began.

The time spent together went uncounted.

But the king could bear the separation no longer, and proposed.

Though the daughter was still mindful of her father’s absence.

The king overbore her objections, and suggested they marry in the ancient way.3

She was as smitten as he.

So the wedding took place by a simple exchange of garlands, with the forest’s denizens, and her deer companions, for witnesses.

Their joy was complete.

The days passed with no external interference.

Sooner than desired, the king was reluctantly reminded of his duties.

Such, the power of love.

Shakuntala was distraught. But how could she leave unless her father returned first?

The king reassured her - never fear, he would send for her soon to be his queen.

Even better, he might return himself with his entourage.

Allaying her concern, he slipped his special royal insignia ring onto her finger - a token to remember him by.

They would be together again, he promised.

The bride of a few weeks hiccuped through her tears, and was held once more.

Lifting her cheek, he smiled at her sad face and roused her courage.

So she wiped her tears and smiled too.

Then he was gone - riding off on his white horse, waving a last goodbye.

She settled down to await her father first, and then, her husband’s return.

Her father came soon enough, it seemed, and when apprised of the tidings, he gave his blessing to the union.

There was nothing more to be done but wait.

Unfortunately, as those in love can attest, the waiting and dreaming take over one’s days, and routines of life become a casualty.

So it was in her case.

Lost in pleasant thoughts of her love, she dreamed the afternoons away.

One afternoon, arrived a famous sage - known for a temper that flared at the slightest pretext.

Tired from his journey, he had hoped to rest at the hermitage.

But the hut was empty.

No one answered his call, offered him water to drink, or washed his feet.

Then, he found Shakuntala beneath a tree, still dreaming.

He called out, but she failed to answer.

Angered beyond belief, he cursed her - that the object of her thoughts forget her instantly.

Snapped out of the clouds, Shakuntala rushed to apologize. ‘

She bowed to the sage, seeking to appease his anger.

The sage relented.

Pleased with her efforts to serve him, he amended his curse - for curses uttered by the wise cannot be undone.

He said, “If your husband sees the ring he has given you, he will remember you.”

This event hastened her father’s preparations for their journey to the kingdom, as they could not wait any longer for the king’s team to fetch her.

They traveled over many days and across unfamiliar terrain.

While crossing a river, Shakuntala had a mishap.

She lost the ring she was wearing - it was a size too big for her lithe fingers.

Aghast, she turned to her father and cried out, “Father, what have I done?”

The sage comforted her and said a few words to distract her worries. Inwardly he was anxious.

They reached the king’s court, hoping for fortune to turn in their favor.

The sage and his daughter, received well at the gates, with all honor due to a sage - were guided to the king’s morning court.

The sage approached the king, with his daughter beside him.

There, for the first time in months, Shakuntala beheld her love.

She was overcome into silence.

The king, however, betrayed neither recognition nor joy at the sight of his wife.

To him, she appeared as no more than the beautiful daughter of this sage - a stranger.

The sage introduced Shakuntala to the king as his wife, asking him to recollect his trip, and their Gandharva wedding.

The king refused to believe him.

He claimed no memory of his time in the forest.

When pleaded with, he demanded: Where was the proof?

Shakuntala, affected by this reaction, could not remain silent any longer.

She walked a few steps toward the king, and attempted, in her soft lilting voice - for she was the daughter of Menaka - to recall him to their blissful moments in the forest.

The king had sympathy for her. Just not the awareness of her.

He addressed her like she was a subject, a beautiful woman worthy of his compassion, and offered her every help to trace her errant husband.

The sage tried to provide more context, but the king became impatient.

He was not willing to contradict a sage, but neither was he willing to accept a stranger as his wife.

Their efforts were exhausted.

What power did a sage and his daughter have to compel this mighty king?

Disheartened, the two returned to their home in the forest, the father consoling his daughter that all would be well some day.

The pain was made more severe now that Shakuntala had discovered she was eating for two.

Months passed, and in time, Shakuntala gave birth to a son.

From the moment of his birth, her child was unique.

As he grew into a mischievous six-year-old, he extended his dominion from his mother and grandfather to the animals of the forest.

One day, deep in the forest, he was engrossed in holding a lion’s mouth wide open with his hands.

Suddenly, he encountered his father.

Taken aback by the boy’s courage, the king enquired what the child was up to.

“I am counting the lion’s teeth,” he replied innocently.

Amazed to find a boy in that fearless position, the king asked for his antecedents.

Boldly the child proclaimed: “I am the son of Dushyant and Shakuntala.”

Hearing his own name, but unsurprised, the king asked to be led to the boy’s home.

There, he called to his wife again - who had suffered immensely for her innocent folly - and repented his conduct.

A fisherman in his land had caught a huge fish, and on cutting it open - the king explained - had found the ring he had given to Shakuntala.

When it was presented in court by the frightened fisherman, the king’s memories had come rushing back.

Racing to her, he had encountered their son and now he begged her forgiveness.

Between laughter and tears, the wife, as many wives are apt to do, forgave her true love.

In an instant, the years rolled back.

With the blessings of the sage, the king, his queen and their young prince returned to the kingdom.

The son grew up to be a brave and just ruler.

In time, his descendants - the Pandavas - would fight the greatest war the land had ever known, and restore righteousness by defeating their evil cousins.

His name?

Bharata.

His land would come to be known as Bharat - the land of King Bharata.

Otherwise known as India.

Notes

I have retold here, a timeless legend of the ancient world - the story of King Dushyant and Shakuntala - that was immortalized in a Sanskrit play by the literary genius, Kalidasa (4th-5th CE). Its first English translation was published in 1789 by Sir William Jones, a pioneer in the field of Indology.

Goethe was a great admirer of this play, praising it in his ‘Italian Travels at Naples’ in 1791. He also composed this epigram

“Willst du die Blüthe des frühen, die Früchte des späteren Jahres,

Willst du, was reizt und entzückt, willst du, was sättigt und nährt,

Willst du den Himmel, die Erde mit einem Namen begreifen,

Nenn’ ich, Sakontala, dich – und so ist alles gesagt.”

It was later translated by the famous Orientalist, Max Muller, in ‘History of Sanskrit Literature’ as:

“Wilt thou the blossoms of spring and the fruits that are later in season,

Wilt thou have charms and delights, wilt thou have strength and support,

Wilt thou with one short word encompass the earth and the heaven,

All is said if I name only, Sacontala (Shakuntala), thee.”

These celestial nymphs are known as Apsaras—and appear throughout mythological stories. Among the most famous are Urvashi, and in this tale, Menaka. Even today, someone might teasingly ask if a person thinks they’re an “Apsara” or “Urvashi”—to deflate pride or hint at vanity.

Tapas in Sanskrit refers to an intense form of meditation or austerity through which people acquire divine powers or blessings.

Known as a Gandharva marriage, it is one of the earliest accepted Vedic wedding rituals, where a couple weds by mutual consent through a private exchange of vows and garlands. Kinda like a modern-day registered wedding - minus the officials, paperwork, and witnesses!

And so Mahabharata Epic was fought. Lord Krishna will help win the land of India.

Thank you very much. Jayshree!