You may have heard of the ancient text, the ‘Gita,’ especially in the context of Oppenheimer’s life. In this post, I provide cultural context and offer perspective on its insights related to ‘work.’ Going forward, I will also include selections from the Gita in my ongoing ‘wisdom’ series."

Context: The Great War

War was finally declared after many injustices were committed by one side against the other, fearing they would stake their rightful claim to the kingdom.

The war was declared between the children of two brothers: a hundred sons1 of one brother pitted against the five sons of another.

Between cousins who grew up, played, and studied together under the same teachers.

Now, their mothers, grandparents, friends, and teachers found themselves on opposite sides with mixed emotions.

Some elders had no choice but to fight for the side they believed in the least due to an oath of loyalty taken for an ancient dynasty.

Others chose to fight on the side of the virtuous five brothers.

The Reluctant Warrior

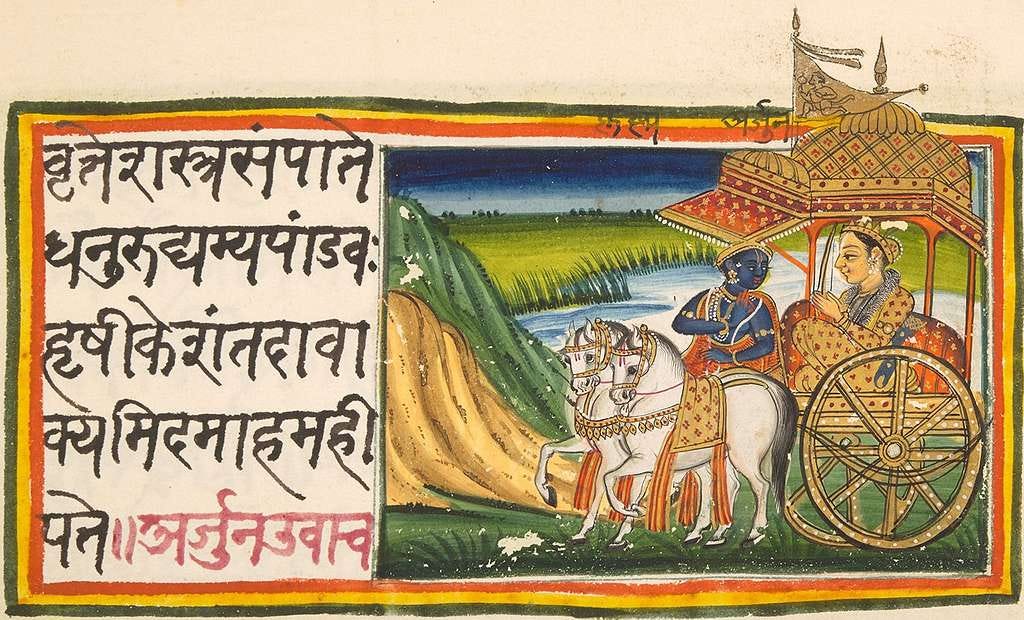

On the first day of the eighteen-day war, as the two armies met on the battlefield, Arjuna, renowned for his bravery, sat motionless in his chariot, his bow and arrow cast aside.

Depressed at the sight before him as the enormity of the situation sank in, he called out to his friend, Krishna, the peerless one, who had agreed to be his charioteer.

“Forgive me, Krishna, I cannot fight,” he said. “What use is the wealth and fame that comes from killing my family? These people are the elders who raised me and taught me all that I know. Am I to take up arms against them and kill them? No, no, I cannot, and will not fight. Let my cousins have the kingdom and its riches. I do not care for it at this cost.”

Seeing Arjuna's despair and his listless form, Krishna admonished him to stop being a coward, as it did not suit a warrior of his caliber.

Krishna then set out to deliver wisdom on the meaning of life, duty, death, devotion, knowledge, and universal truth.

At the end of this lengthy dialogue, Arjuna’s doubts were resolved, and he arose and picked up his arms.

Renewed, revitalized, and confident, he stood tall and resolute in his duty to restore the balance of good against evil, as directed by Krishna, the arbiter of righteous action in the Universe.

Arjuna was the key reason the five brothers achieved victory in the great war against all odds, thus defeating their evil cousins.

The Philosophy

The dialogue between Arjuna and Krishna, in the form of questions and answers, is known as the ‘Song of 'God’ or the ‘Gita’ (Song) for short.

The 700 verse marvel in Sanskrit is considered a gem among Hindu philosophical texts, as it encapsulates all its core tenets in a unified manner.

These verses have been read by many scholars, local and overseas, and translated nearly 2000 times in over 70 languages globally.

Its first English translation was published by British writer, typographer and Orientalist, Charles Wilkins in 1785 who is also credited with coining the term ‘Hinduism.’

The interesting part of the collection is that it is open to interpretation and every translation offers a new perspective based on the author’s philosophical understanding and beliefs.

For beginners and philosophy enthusiasts, any widely acclaimed translation will provide a summary understanding. Advanced readers, however, should also consult the original verses with a word-by-word English translation to reflect on its insights independently.

Cultural Adoption

The scene on the battlefield between Arjuna and Krishna has been depicted in various art forms in India and is commonly gifted to others and displayed in Indian homes. It is often interpreted as the battlefield of life, with the wisdom being applied to general life situations.

Many of the Gita’s famous verses are widely known across India, even if a person has not read the entire text, as they have been spread through stories and word of mouth over the ages.

In some families, retired elders read a selection of verses from the Gita daily, while others organize joint reading sessions with other retired elders in the community.

More enterprising individuals arrange sessions—whether virtual or physical—where spiritual teachers and monks are invited to explain the meaning of the Gita in summary, using selected verses of their choice.

Gandhi was one of its notable daily readers and frequently highlighted the central role its teachings played in his life. He also translated the text into English.

With this context, I present a modern take below, combining multiple verses and grouping the meaning to illustrate core concepts.

Why work?

All work, even that which is good, is tainted, just as fire is covered by smoke.

However, this does not mean you should abandon the work that is assigned to you by nature, duty, position, or purpose in life, even if it has imperfections.

Just as humans affect microorganisms merely by breathing, no work is without fault.

Understanding this, the wise do not avoid action but instead act with purpose and intent for the benefit of others (humanity).

Great individuals become role models for others to follow, and thus, it is crucial for them to show the right way of (right) action.

How to Work?

Recognize that you have the right to work, but not the right to its results.

Being attached to results binds you to the world, distances you from knowing your true Self, and causes misery.2

The wise, understanding this truth, work with detachment—doing good for its own sake, not for the rewards3 it might bring.

However, it is even more important to avoid inaction.

No being can live without performing action—in fact, action is necessary even to maintain the body.

Consider me,4 the Universal Truth.5 In the three worlds, I have no duties and nothing to gain or lose from working.

Yet, if I were to stop working, the world would fall into chaos.

Thus, I am constantly engaged in work.

So too, should humans act, without becoming overly attached to the results.

Achieving Balance in Life

A wise person avoids extremes in all aspects of life, whether it be in eating, exercising, or working (i.e., desires).

For instance, eating too much or too little, subjecting the body to extreme forms of exercise or yogic practices, or working excessively or insufficiently—all of which can be driven by unchecked desires—tends to cause more harm than good.

Moderation and balance help a person attain a state of calm in both mind and body.

This balance leads to a person becoming a ‘stith pragyah’6—someone who has attained a state of steady, unshakable knowledge and understanding, remaining unaffected by external circumstances and emotional disturbances.

Such a person possesses self-control, remains focused on their higher spiritual purpose, and finds satisfaction within themselves, rather than from external achievements.

Achieving this state of balanced wisdom should be the goal of a wise person.

I hope you enjoyed this take!

Further Reading

You can search for original translations online as AI searches also give you quick answers now. For instance, one search term ‘what does Gita say about work?’ yields a quick summary with sources.

If you are interested in some authentic translations, check out these authors:

See this reference for how they had 100 sons. Remember, some believe the story is allegorical.

This verse is one of the most famous and illustrates the concept of detachment. It is also one of the most difficult to understand, interpret, and execute.

The concept is that actions bind a human. Only those who are not bound by the results of their actions can be truly free.

Krishna/God/Universe/Spirit

Anything powerful you believe in!

Sanskrit, stith = "steady," "fixed," or "established."; pragyah = "wisdom" or "intelligence."

Outstanding!

Thank you for sharing this.